They Cleekhim Here, They Cleikum There . . .

Added on 11 November 2020

The true story of Airntully’s “Cleikim Inn” revolves around this formidable, fictitious, character, Meg Dods.

In its edition of 6th April 1854, the Perthshire Advertiser reported the death the previous Friday of a centenarian, Catherine Henderson or Low, in Airntully. Actually 103, she had lived cradle to grave in the parish, to the best of the PA’s knowledge (no sniggering there, you who still buy a Tuesday or Friday copy). She had been sustained latterly by a small weekly allowance “from the Murthly family”, possibly a reference to Catherine being a pensioner of the Grandtully Mortification Trust. Her address was given as the Cleikhim Inn.1

Over the years there have been many such suggestions of a hostelry at Cleikhimin on the northern edge of the village. And yet . . . evidence?

Cleikhimin is not a common name for a Scottish village. In fact, there are only three, with the others in: North Motherwell on the A723, near Carfin; and Lauderdale, just south of Carfrae Mill off the A68. Both spelt ”Cleekhimin”. All three have been associated with inns. The Ordnance Survey Name Books are a fantastic resource for researchers, for us all. They were compiled by the military surveyors mapping Scotland county by county, parish by parish in the late 1850s, early 1860s. Landowners and local worthies would be consulted on the spelling of everything - hills, lochs, rivers, woods, settlements, castles, ruins, stone circles etc - that would appear on the maps. Collectively, the Name Books offer a richly detailed gazeteer. The entries for Cleekhimin are:

Cleekhimin (Motherwell) : A little village on the side of the Hamilton & Edinburgh Road. There was till recently a toll gate here. There is a School and some Public Houses here.2

Cleekhimin (Lauderdale) : A small house at one time an Inn, but at present used as a Coffee house. Cleekhimin Toll Bar (Lauderdale) : A Toll bar with house, Stable and garden attached. (A separate property and ownership to the inn.)3

Cleikhimin (Airntully) : Several dwelling houses situated a little to the north of the Village of Airntully.4

All three settlements lie beside old, aye even ancient roads. The one running through Airntully was known as the pre-turnpike road from Perth by way of Stanley and on straight through present day Douglasfield Farm to the ferry at Boat of Caputh. However, in the early 19th century a new turnpike road was laid parallel to this (today’s B9099) by-passing Airntully. Contrastingly, in Motherwell and Lauderdale, the old roads were simply upgraded under the Turnpike Roads Act of 1751, with toll houses erected at significant junctions. And though something of a sweeping statement, it’s safe to say it was a rare toll bar that wasn’t an inn or had a “back parlour” or at the very least a howff nearby, legally or not.

Where inns were known on by-passed pre-turnpike roads, such as Murthly Inn at Kingswood, theirs became a story of gradual decline after the Turnpike Act. (Murthly Inn suffered a double whammy: carting traffic through Kingswood ceased when the ferry at Boat of Murthly was closed to public use in 1809. By the time of the OS mapping surveys it had closed altogether, and the name transferred to the inn, formerly known as Strathern’s, beside the turnpike at the village crossroads.)

This was not Airntully’s fate: some might say Cleikim Inn was yet to get going.

The First Statistical Account of Scotland’s report for the Parish of Kinclaven in 17975 mentions only one hostelry, an inn serving the ferry across to Meikleour (three ferries, actually: one for people, one for horses, and one for carriages). The anonymous author, “A Friend to Statistical Enquiries”, had much to say about “Arntully”, then a settlement of 60 to 70 dwellings, and none of it good. He particularly deprecated the plight of poor tenants with no place for their dung heap but at the front of each house.

In the New Statistical Account’s entry of 18436 the opportunity for a pint had risen by 100%, thanks to an inn close to the Kirk O’ Muir, for the convenience of travelling Secessionists (from as far as the west of Scotland and Ireland). Still no mention of a Cleikhim Inn, a mere 11 years before Catherine Henderson’s death notice in the PA.

Motherwell’s Cleekhimin had several public houses, and the one which outlasted the others was called The Cleek-Him-Inn. Playing, perhaps, on cleek/cleik a: the act of cleiking, attaching something. (Although Jaimieson’s Dictionary of the Scots Language does not fully support this definition.) A persistent story has it as a coaching inn. It was directly on the coach road from Hamilton to Edinburgh, which had a punishing series of climbs all the way from the River Clyde until the route levels out high on the Shotts Plateau. To help the puir cuddies, it was said, an additional pair would be cleiked into a stagecoach’s traces, while the passengers supped, and the coachman no doubt had a stiffener or three for the next leg: the long five mile pull up to New Inns (present day Newhouse) to connect with the Glasgow to Edinburgh road.

A good story, even a convincing one for anyone who has ever cycled home from Hamilton to Newhouse . . . on a Sturmey-Archer 3 Speed gear. Further credence comes from an old fiddle tune “Cleek Him Inn” collected by Robert Bremner in his Scots Reels of 17577, commemorating it as a coaching inn.

(When I knew The Cleek-Him-Inn in the late 1960s it was a flat-roofed one storey howff, offering no evidence of outbuildings or stables, but hosting an evil reputation. Cleeking seemed to have morphed by then to the act of grasping someone by the back of the neck and head-butting him. Which meaning is supported by Jaimieson. Kind of.)

Airntully’s Cleikum Inn came into being on 18th April 1878. That’s the date on a 19 year lease of the property, and under that name for the first time: “House, [work] Shop, half of Byre and the old Byre or barn and pendicle of land about three acres”, accepted by Andrew Young from Sir Archibald Douglas Stewart.8 However, Andrew Young was a joiner, not a publican. As reflected in his annual rent of £11 (subsequently reduced to £9 10/- a decade later). By contrast, the rent for Murthly Inn at this time was £37 pa.

What’s going on? Dear Reader, welcome to Scott-land . . .

Sir Archibald liked to rename things. Starting with himself. When he inherited the baronetcy in 1871 on the death of brother William, he exerted authority by insisting everyone refer to him as ‘Sir Douglas’. Not gainsaid on that, surprisingly (Laird, eh) he declared Murthly henceforth would be Murtly. (Which never made any sense. Slightly more authentic might have been Murthlie, for at least that spelling appears on old maps, and would have chimed with other Perthshire place names, such as Pitlochrie and Trochrie.) Dalpowie Lodge became Birnam Hall. Strathbraan estate was to be known as Braandale. North Airntully Farm changed to Stewart Tower. Garth Farm became Drummond Hall. The Old Mill of Airntully was to be known as Fitzalanby. . . And so on.

In 1878, when Michael Griffiths surrendered his lease of Cleikuminn pendicle (as it appeared in the Rental Ledger) Sir Arch . . .sorry, Sir Douglas seized his chance to impose a more literary spelling, and association, on one of his properties.

The Cleikum Inn features in Sir Walter Scott’s novel, St Ronan’s Well (1823).9 It is run by a “Landleddy”, Miss Margaret (Meg) Dods, and its signboard illustrates the origin of its name by showing a local saint, Ronan, catching (cleiking) the Devil by the ankles with the crook of his staff, and casting him down. Mistress Dods runs a clean and orderly establishment where the Cleikum Club meets to sample the very best of Scottish gastronomy in convivial company. Owing to the popularity of Scott’s novel, and even more to a collection of recipes, The Cook and Housewife’s Manual,10 supposedly written by Mistress Dods in 1826 (actually by Mrs Christian Isobel Johnstone - an early example of tie-in merchandising that ran through a dozen editions or more) several pubs across Scotland rebranded themselves as Cleikum Inns, and there was even one in Fremantle, Australia. The latter opened by an immigrant couple from Scotland who had arrived in 1830. Their name? Dodds.

In Airntully, however, Sir Douglas’ ambition got no further than renaming a joiner’s workshop. Briefly at that: the Rental Ledger of 1884 notes Andrew Young as “tenant of the pendicle at Cleikuminn.”

The PA’s mistaken attribution in 1854 may have been a homophonic lapse. Like so many others, including Rev. Routledge Bell, minister of Caputh, in the Third Statistical Account as recently as the 1960s, it is so easy to hear “Cleekimin” and transpose to “Cleikhim Inn”. In 1854 association with that byword for conviviality, the fabled Cleikum Club, may also have played on the writer’s mind.

What then is the true derivation of “Cleikimin”? A recent study of Berwickshire place names gives us the following:

This word appears to be derived from two Gaelic Words. Glaic, a hollow a corner or a Small dale; and Iomain a chase or flight Thus Glaiciomain may denote the Glen or corner of the chase or of the flight. It may also be a corruption of Glaicamhuin, Signifying the river of the corner or of the dale.1

Cleekhimin in Lauderdale lies at the corner junction of two ancient roads, and is bounded on a third side by the Cleekimin Burn. As in the Armstrong Brothers' map of 1771, here.

Cleekhimin, near Carfin, also lies at a corner junction. This section from William Forrest's Map of Lanarkshire of 1816 shows it bounded by roads on three sides and close to the Calder Water. As the ground either rises or falls from th ere it would have been a hollow or dale some time ago. However, the land around has been re-shaped and traduced by two centuries of industry, with competing collieries, railways, iron and steel works.

ere it would have been a hollow or dale some time ago. However, the land around has been re-shaped and traduced by two centuries of industry, with competing collieries, railways, iron and steel works.

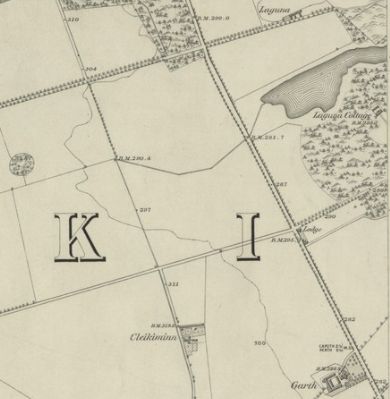

Cleikhimin, by Airntully, again is at a corner. Although there is no particular water course now, the land would have drained to nearby Patterloch (which then lay between Laguna Farm and Laguna Cottage) shown on the 1st Ed. OS map of 1864 below. The connection would have been more apparent before the turnpike road (B9099) severed it in the early 19th century.

It would appear the connection between the name and subsequent inns is either coincidence (Lauderdale), clever word play (Motherwell), the Perthshire Advertiser hearing what it wants to hear (Airntully), or a pretentious laird.

Notes & Sources

1. Perthshire Advertiser, 6th April 1854. Story subsequently reprinted in Dumfries & Galloway Standard, 12th April.

2. https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/

Free website with acces to Ordnance Survey Name Books: Lanarkshire, Vol 05.

3. Berwickshire, Vol 40

4. Perthshire, Vol 11.

5. Statistical Accounts of Scotland: OSA Vol XIX 1797, p333.

6. Statistical Accounts of Scotland: NSA Vol X 1845, p 1135.

7. Traditional Tune Archive: www.tunearch.org

8. Murthly Castle Archive: Box F, Airntully Leases.

9. Sir Walter Scott, “St Ronan’s Well” (Henry Froude, OUP, 1912)

10. Quoted in F. Marian McNeill, “The Scots Kitchen” (Mayflower Books, 1974)

11. Recovering the Earliest English Language in Scotland: evidence from place-names. 2020. Glasgow: University of Glasgow. https://berwickshire-placenames.glasgow.ac.uk

© Murthly History Group