Birnam on Steroids

Added on 22 April 2020

I was opening another map in the castle archive. The ninth or tenth of the morning. It was not scrolling out as an OS map of the estate, however. As large, yes, but hand-drawn. A word blazed out – 'Birnam'. A much bigger Birnam than the one we know today.

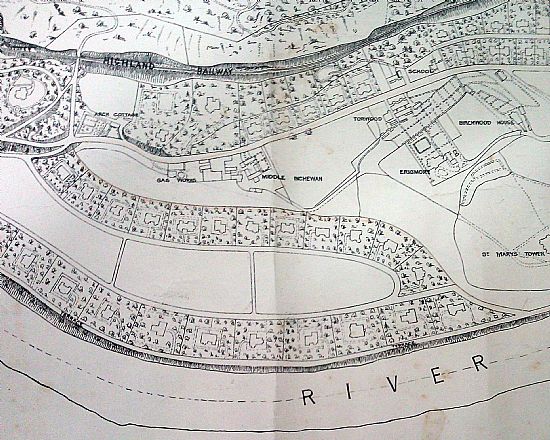

What I had, measuring 110cm x 75cm, was the "Plan of Ground to be Feued at Birnam on the Estate of Sir Douglas Stewart Bart. of Murthly and Grandtully". Dated 12th February 1876. (Section below.)

The plan was the work of A & A Heiton, Architects, of George St in Perth. (Interesting. The Heitons, pere et fils, have certainly left their mark across Perthshire, but in singular buildings not planned villages.) It showed a Birnam that stretched miles way to the east, rows of villas along the turnpike road, and parallel to them a similar row on terraces beside the Tay. All the way out to the present junction with the A9.

The scale on the plan was one inch to 200 feet. From this it was easy to work out each villa in this section would have an acre of ground. Eat yer heart out Druid's Park inmates. Upwards of eighty new homes. A fantasy. Not so much Brigadoon-sur-Tay as Birnam-on-Steroids.

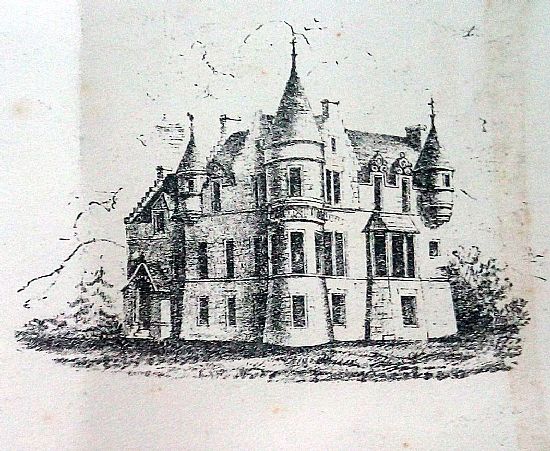

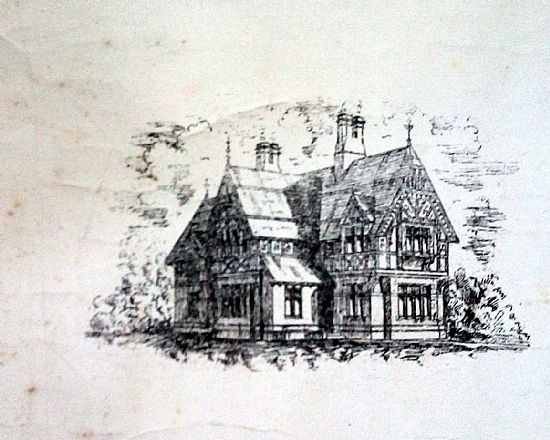

And there were more villas in the section going east again from the junction, right out to Ringwood. These had much larger, irregular wooded plots. A sylvan suburb laced with carriage drives beyond the neat and serried rows of the village. Around the plan, the Heitons had dropped in seven detailed illustrations of the villa types they could provide, such as the one below.

Putting the plan to one side, reluctantly, for it is a beautiful piece of work, I delved back into the records.

Putting the plan to one side, reluctantly, for it is a beautiful piece of work, I delved back into the records.

Archibald Douglas Drummond Stewart (1807 - 1890) inherited the baronetcy and estates of Grandtully, Strathbraan, Murthly, and Airntully on the death of his brother, Sir William, in April 1871. These were still locked together in the entail created by John Steuart, ‘Old Grantully’, back in 1717. That is, not to be split asunder, sold off in lots or gambled away. A fine, patriarchal concept, the entail: Your family's lands, held in trust for succeeding generations. Yet by the early part of the 19th century entailed estates were increasingly seen as a burden, and not just for lairds . . . for the country. A brake on improvement and progress.

An Act of Parliament in 1848 signalled a change. It allowed proprietors of entailed estates to lease land for building, for up to 99 years, yet forbade outright sale. Estates could be improved, businesses encouraged, amenities provided, but the essential nature of the estates, the land, rivers, and lochs were still there to be owned by the next in line. Should a feuar default on payments or break the conditions of his lease, the land and everything on it could end up back with the laird. (This happened to James Baxter, who built Peacock Cottage on two acres of ground in Gellyburn feued from Sir William. He got so heavily into arrears on his annual payments the estate eventually reclaimed both the land and cottage.)

By August 1872 Sir Archibald’s solicitors had prepared a 'Petition for Authority to Feu' and submitted it to the Sheriff Court in Perth. In doing so he was following William's example: who had submitted a petition in 1857 for permission to lease out the ground around Birnam Station, thereby creating the village we know today. ( The same William who had for years strenuously opposed having the Perth to Dunkeld Railway across his lands, spoiling his Deer Chase and other recreational ground. Until that Kerching! moment sometime in 1854, when he realised how much money could be made from having the station on his side of Birnam, east of the Inchewan Burn, the boundary with Atholl estate.)

Notice had to go to the next Heir of Entail. As Sir Archibald was still a bachelor, this was ten-year-old Walter Thomas James Fothringham of Pourie, in Angus. Walter’s guardians had fourteen days to lodge an objection, but none was forthcoming. (Cynically? ‘Gang yersel, Archie boy!’ This was going to increase the value of the estates. And Archibald was already in his sixties.)

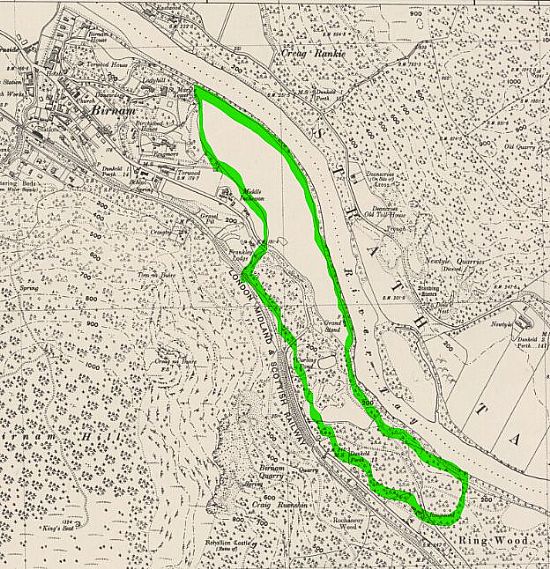

Archibald had gone much further than his elder brother, however, asking for permission to feu considerable portions of Grandtully and Strathbraan estates, as well as Murthly. The ask for Murthly fell into two distinct lots: 160 acres of the lands of Inchewan (see map below); and approximately 39 acres of the lands around Murthly Station in Ardoch, Burnbane, and the hamlet of Gellyburn.

Permission was granted on 21st April 1873. With the proviso that the Inchewan ground closer to the village should fetch a minimum of £8 per acre per annum (out towards Ringwood this dropped to £7 per acre). The land around Murthly Station could go for £3 per acre.

Permission was granted on 21st April 1873. With the proviso that the Inchewan ground closer to the village should fetch a minimum of £8 per acre per annum (out towards Ringwood this dropped to £7 per acre). The land around Murthly Station could go for £3 per acre.

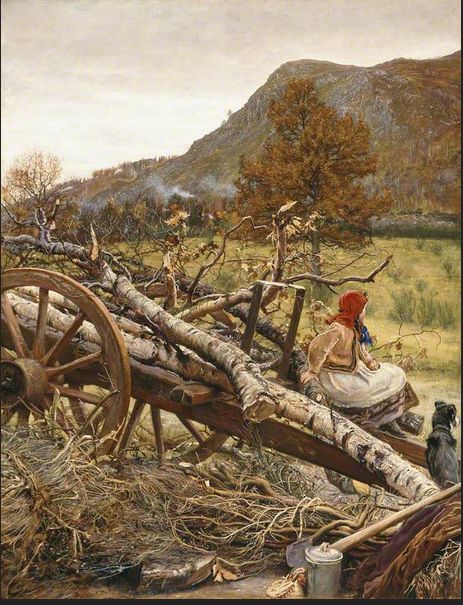

The largely undeveloped nature of the ground east of Birnam Station then was perfectly caught by Sir John Everett Millais in one of his early Perthshire landscapes, 'Winter Fuel' (1873). Below, left.

In his thoroughly well-researched booklet, John Everett Millais and Dunkeld (Culross, 1985) WJ Eggling states this was painted “from close to Erigmore.” (Eggling's detective work can actually take you right to the spot where Millais would have set up his easel for many of the landscapes he painted in this area.)

Having so quickly secured his permission to feu, why did it take Sir Archibald another three years to secure the services of an architect and come up with his grand plan for developing those 160 acres? Well, he was a single man in possession of a good fortune . . . although more in need of an heir than a wife (of course, being so unlike his brother, the latter would have to come first). That was one priority. Then Margaret Wilson barged into his life.

Margaret had no designs on Sir Archibald. Just the estates. Claiming to be the widow of Major William Stewart VC (1831-1868) she wanted their son’s inheritance. Now Sir Archibald would have remembered an invitation to his nephew's wedding (and carefully noted the cost of any small present in his accounts). However, it turned out this was a Scotch Marriage: a commitment between William and Margaret made in the presence of witnesses, but without any paperwork. Cue m'learned friends.

Margaret had no designs on Sir Archibald. Just the estates. Claiming to be the widow of Major William Stewart VC (1831-1868) she wanted their son’s inheritance. Now Sir Archibald would have remembered an invitation to his nephew's wedding (and carefully noted the cost of any small present in his accounts). However, it turned out this was a Scotch Marriage: a commitment between William and Margaret made in the presence of witnesses, but without any paperwork. Cue m'learned friends.

The resulting litigation was a drawn-out, nasty affair in Edinburgh's Court of Session. Labelled the "Murthly Marriage Case" by the press, it was only resolved by a decision in the House of Lords in 1875. (I really should write it up for this blog, but no one comes out of it well. Least of all the VC, who couldn't defend his honour, being dead and thus slanderable. Desperate to hold on to everything, not give so much as a mite to the widow, Major William's uncle and step-brother, Franc the Yank, thoroughly Cherry Blossomed his character.)

Meanwhile, Sir Archibald courted Hester Mary Fraser of Buncrew. They were married on 4th May 1875. He was 68, she was 34.

Why was the grand plan never put into practice? There are gaps in the archived records. Two theories are worth airing. Perhaps it was the Law of Supply and Demand, but applied inversely. Sir Archibald (who had a reputation for grasping) may have demanded too much, but more importantly, too early, and found that the supply of Lords Molloch, Lady Mufty Trumpingtons, Colonel Mustards, the McClarty of McClarty of that Ilk et al, necessary for such a grand plan, just did not materialise.

They would come. But it would be more than a decade before Andrew Lang (1844 – 1912), noted author and anthropologist, would write impishly that anyone seeking to understand the British upper class need only spend August in the Birnam Hotel.

Perhaps there was a more existential reason. As the years went by and Sir Archibald and Lady Hester settled into childlessness, faced with being the Chingachgook of the Stewarts of Grandtully, could he thole doing all that only for the boy from Pourie to inherit?

Andrew Heiton Jnr (1823 - 1894) would design many grand buildings, such as Dundarroch, the Atholl Palace, and Bonskeid House in Pitlochry, and St Mary’s Monastery in Perth, but his only success in Birnam remains the station. His designs for grand villas in one and two-acre plots there came to naught.

Andrew Heiton Jnr (1823 - 1894) would design many grand buildings, such as Dundarroch, the Atholl Palace, and Bonskeid House in Pitlochry, and St Mary’s Monastery in Perth, but his only success in Birnam remains the station. His designs for grand villas in one and two-acre plots there came to naught.

© Murthly History Group