The Dandy Fechters - Part 1

Added on 22 September 2020

Young William Drummond Stewart, second of Sir George and Lady Catherine’s five sons, born Boxing Day 1795, was tutored at home before being sent away to Westminster School. Not to Eton, like older brother, John; apparently his parents saw enough of his adventurous character by age 10 to agree he should go into the army and opted to defer any real expense until then. 1

In 1813, Sir George purchased a cornetcy for him in the 6th Dragoon Guards for £750. William was just 17 and had set his foot on the lowest acceptable rung of a military career, for a gentleman.

However, William soon chafed at life in the 6th, on garrison duty. Could Papa not buy a position in the Hussars instead? Preferably the 15th: such splendid uniforms, its officers really cut a dash. Moreover, they were with Wellington and the Peninsula Army, winning battle after battle, pushing Napoleon’s army out of Spain. William would have known of the 15th’s famous charge at the Battle of Sahagun on 21st December 1808, just before his 13th birthday. While some muttered about “fops and dandies” (apart from being so colourfully attired the hussars were the only regiments in the British Army permitted to grow moustaches at that time) these officers undoubtedly led a fighting regiment. That charge had “set the standard” for British cavalry for the whole of the Peninsula Campaign.2

However, William soon chafed at life in the 6th, on garrison duty. Could Papa not buy a position in the Hussars instead? Preferably the 15th: such splendid uniforms, its officers really cut a dash. Moreover, they were with Wellington and the Peninsula Army, winning battle after battle, pushing Napoleon’s army out of Spain. William would have known of the 15th’s famous charge at the Battle of Sahagun on 21st December 1808, just before his 13th birthday. While some muttered about “fops and dandies” (apart from being so colourfully attired the hussars were the only regiments in the British Army permitted to grow moustaches at that time) these officers undoubtedly led a fighting regiment. That charge had “set the standard” for British cavalry for the whole of the Peninsula Campaign.2

Sir George’s purse took another, bigger hit. Although that cornetcy in the 6th could easily be sold on (minus the requisite fee to the regimental brokers, of course) a lieutenancy in the Hussars would cost about £1,000. And it would not be cheap equipping William in the extravagantly theatrical uniform of the 15th (The King’s) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons, to give its Sunday-going-on-church-parade title. Lt. George Woodberry of the 18th Hussars, William’s contemporary, but already a year ahead of him in campaigning, gives a clear accounting of what it cost to be a gentleman in the cavalry, in his journal, With Wellington’s Hussars in the Peninsula and at Waterloo.3 After buying a commission, dress and undress uniforms, a gentleman must provide his own curved 1796 pattern sabre and brace of pistols; his charger, spare horse, pack horse, and their saddlery; camp equipment, and possibly a cart. George or rather, his father spent £488 here. He also needed a servant, at £100 a year, who might have had to find his own clothes and food out of that, “but when in England I am to find him a bed.”4 His bills in the officers’ mess would run at £500 a year.

Given Woodberry’s experience, at a conservative estimate it cost Sir George and Lady Catherine £55,000 in today’s money to establish William as a lieutenant, and sustain him for his year in France. His pay was £164 5/- (around £7,000).

Lieutenant Stewart was duly commissioned on 6th January 1814 and left for France to join his regiment. The 15th Hussars, as they were known to everyone (although not officially designated as such until 1861) were then somewhere in the foothills of the Pyrenees. In field campaign mode, skirmishing with Marshall Soult’s chasseurs. On arrival, William was no more than an unchancy cannon ball or musket shot away from being in sole command of a troop of around 60 “sabres”. He was barely 18, and as green as Maureen O’Hara’s eyes.5 Little wonder that Wellington railed against a system where fops and dandies bought their rank, and engineered advancement through family connections and patronage (while doing nothing to change it).

Lieutenant Stewart was duly commissioned on 6th January 1814 and left for France to join his regiment. The 15th Hussars, as they were known to everyone (although not officially designated as such until 1861) were then somewhere in the foothills of the Pyrenees. In field campaign mode, skirmishing with Marshall Soult’s chasseurs. On arrival, William was no more than an unchancy cannon ball or musket shot away from being in sole command of a troop of around 60 “sabres”. He was barely 18, and as green as Maureen O’Hara’s eyes.5 Little wonder that Wellington railed against a system where fops and dandies bought their rank, and engineered advancement through family connections and patronage (while doing nothing to change it).

With Wellington anxious to begin his spring offensive and bring Soult to battle William had only a few weeks to get to know his men, learn the drills, evolutions, and signals, cope with his turn leading a night piquet, and get used to reveille at 3am. As Woodberry noted, “The duties of hussars in the field are so various, and require so much practice and experience that (enough) opportunities cannot be taken . . . for training.” 6William would have no parade ground, no drill yard; all of his training would, often, be under live fire. Luckily, his squadron commander, Captain Thackwell, assigned him Richard Ryder,7 an experienced trooper, as his ‘groom’.

Born in England in 1781, whereabouts unknown, Richard had joined the Royal Marines at 15. He was at the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801, when Nelson destroyed the Danish fleet. Richard and the admiral both suffered from seasickness but, unlike Nelson, who quickly found his sea legs after a run ashore, his bouts were progressively debilitating. Enough so that he was discharged from the service soon after. The sea having rejected him, Richard surrendered to nominative determinism8: he joined the cavalry, the 15th Hussars.

On 21st December 1808, during the first phase of the Peninsula Campaign, the 15th carried out a tough night march in heavy snow to surprise the French at Sahagun in northern Spain. Although under strength, with only 350 men and horses fit for the attack, the Hussars charged a cavalry brigade (double their number) just before dawn, routing them. The official account does not bother with the number of French killed; but two colonels, eleven other officers, and one hundred and fifty-four other ranks were taken prisoner; one hundred and twenty-five horses were captured along with some mules, and the baggage train. The regiment lost two privates and four horses. The 15th’s other honours during the second phase of the campaign include the battles of Vittoria and Salamanca.9

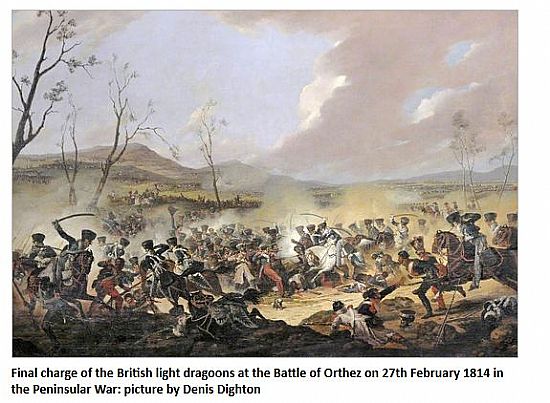

Richard Ryder was, therefore, an ‘old sweat’ (although only 32) a battle-hardened, seasoned campaigner. Exactly the type a good commander would assign to steady a fresh and impressionable young officer. Within a few weeks, the 15th was in the thick of it again. Lieutenant Stewart’s first experience of the fog of war was at Orthèz when, in early February, Wellington began a series of manoeuvres over several weeks designed to force a reluctant, but wily, Marshall Soult into a decisive engagement.

This finally took place on the 27th. The terrain was not conducive to cavalry, being strewn with ditches and walls, and the 15th was not heavily engaged. In subsequent weeks, however, various squadrons had a series of encounters, sharp skirmishes, at Grenade, St Gernier, Tarbes, Tournefeuille, St. Simon, and Gagnac. Captain Thackwell was given a field promotion to brevet-Major, and the regiment was singled out by Lord Edward Somerset, general commanding the brigade, for its conduct.10 The pace of William’s on the job training was fierce, fast and furious. And Marshall Soult was being forced back to Toulouse.

This finally took place on the 27th. The terrain was not conducive to cavalry, being strewn with ditches and walls, and the 15th was not heavily engaged. In subsequent weeks, however, various squadrons had a series of encounters, sharp skirmishes, at Grenade, St Gernier, Tarbes, Tournefeuille, St. Simon, and Gagnac. Captain Thackwell was given a field promotion to brevet-Major, and the regiment was singled out by Lord Edward Somerset, general commanding the brigade, for its conduct.10 The pace of William’s on the job training was fierce, fast and furious. And Marshall Soult was being forced back to Toulouse.

Toulouse, famously, is a battle that need not have happened, Napoleon having abdicated four days earlier. On 10th April, 1814, the 15th was ordered to support an advance by the infantry. William and Richard had to grin and bear it as the regiment suffered casualties to men and horses when raked by cannon fire, unable to engage directly with the enemy.

With Napoleon corked and bottled on Elba, the British parliament sought a peace dividend through an immediate culling of its huge expenditure on both army and navy. The 15th got off lightly, losing only the four troops of reinforcements it had received before Toulouse; the remaining eight troops were needed to support the civilian authorities in Ireland. Doubtless the Officers’ Mess, when they returned to barracks in Hounslow, rang to the ironic toast of, “The Irish! God bless ‘em.”

The regimental history has nothing at all to say about Ireland: it is often non-committal or, when forced, terse (as we shall see in Part 2) about its policing role. The 15th’s history only picks up with Napoleon’s return to France in March 1815.

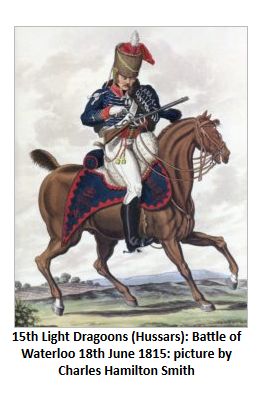

Waterloo. During the night of 17th June the regiment was exposed to a torrential downpour in a field of rye. William, too, kept a journal (although not assiduously, not at all like George Woodberry). He wrote of those miserable hours as “the most dreadful bivouac ever experienced”11 Having first tried to shelter under a pile of wet straw with Captain Thackwell he added, “We were obliged to wander up and down in the mud to produce some species of circulation in the blood which we knew not how soon should flow.” The call, “To horse!” at 3am must have been a blessing. Breakfast was “a small piece of brown unleavened bread, sent by the Colonel . . . divided among the officers like a Last Supper. Each eager to snatch at what a well brought up pig in England would have voted a nuisance.”12

As the day wore on William could only have had the haziest notion of how such a vast battle was progressing. The 5th Brigade comprising the 7th and 15th Hussars, along with the 13th Light Dragoons, was stationed to the rear of the Hougoumont chateau. There he was perceptive enough to notice that Wellington kept visiting: “The anxiety of the Duke seemed often to lead him there to what he called the key of the position.”13 Later, the brigade was manoeuvring to charge ten squadrons of lancers beyond the Nivelles Road when “ . . . a large body of Cuirassiers and other cavalry were seen carrying all before them on the open ground between Hougoumont and La Haye Saint, and their lancers were shouting in triumph. The brigade instantly moved towards its former post, and the 13th and 15th charged and drove back the Cuirassiers, with the most distinguished gallantry, for some distance.”14 Open ground! The regiment made charge after charge upon infantry and cavalry, throughout the afternoon. Forming for yet another charge it came under heavier fire, including artillery. “Here we lost (Major) Thackwell, only wounded, (Lieutenant) Buckley dead, (Captain) Whitford wounded and (Lieutenant) Sherwood killed.”15 William’s horse was shot from under him and he then was pinned down by infantry fire. During this time, he watched as Sir Colquhoun Grant, commanding the 15th, “lost five or six horses in quick succession”, and two men at his stirrup. Re-horsed, William was sent to round up stragglers, but could find no more than nine comrades. By this time “the enemy cavalry . . . began to show symptoms of the most disorderly flight”: the battle was won. William found the brigade position. He lay down, “and slept on the ground from twelve until three the next morning.”16

The 15th Hussars lost 28 men and forty-two horses killed; a further fifty were wounded along with fifty-two horses. 17The following day, the regiment joined in the pursuit of the wreck of the Grande Armée. It would remain as part of the army of occupation until May 1816, when ordered back to England. Once again, policing duties saved it from being disbanded or severely reduced. The toast in the Officers’ Mess this time was, “The machine breakers! God bless ‘em.” Sent to Nottingham, Birmingham and Wolverhampton as heroes of Waterloo, the 15th helped supress several riots and disturbances among factory workers. Towards the end of the year, however, parliament did take its dividend. The regiment suffered a reduction in force, to eight troops of just 62 men, and eight horses apiece. Richard Ryder was one of those discharged. Without a pension.

At this point William stepped in and engaged Richard as his servant. Who we next hear of almost three years later, in an extract from the parish register of Little Dunkeld in 1819, regarding a marriage: “February 12th, Richard Rider servt. Murthly and Anne Logie servt. there. No objections.”18

It didn’t take the old soldier long to get his feet under the table.

End of Part 1.

1.Stewart Heritage by Charles Kinder Bradbury & Henry Steuart Fothringham (Braykc publishing 2016) p278

2.Quoted by John Mackenzie in Britishbattles.com.

3.With Wellington’s Hussars in the Peninsula and at Waterloo: the Journals of Lieutenant George Woodberry, 18th Hussars, 1813 -15 ( Ed. Gareth Glover, Pen & Sword, 2017)

4.Ibid, p

5. Anyone of my vintage would probably know more about the life of a cavalryman from watching John Ford’s trilogy: Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, and Rio Grande. Ford is particularly good on the callowness of young officers, and of the need to give them their chance. Besides, has there ever been anything greener . . .

6. Woodberry

7. Ryder eventually became Rider on his move to Murthly, beginning with the record of his marriage to Anne Logie in 1819. Subsequently, his daughters gave Rider as their maiden name to the parish record, and that is the spelling on his death certificate, and in the news item carried in so many newspapers. However, it is given as Ryder in the Census of 1841, presumably Richard spelling it out for the census taker. The clincher is to be found on his Waterloo medal, where Richard Ryder is stamped around the edge: Waterloo Medal Book [Mint 16/112/27].

8. Nominative determinism: a phrase popularised by the New Scientist pointing out how often someone’s surname seems to determine their role in life. For another example see citation below for Richard Cannon, author of a series of regimental histories.

9. Historical Record of the Fifteenth, or King’s Regiment of Light Dragoons, Hussars 1759 – 1841 by Richard Cannon (John W Parker, London, 1841).

10. Ibid,

11. The Waterloo Journal of Sir William Drummond Stewart transcribed by Henry Steuart Fothringham (Journal of the Stewart Society, 1971) p.168. (If this seems a bit much from someone who had seen all of five months campaigning, and through spring and early summer in the south of France at that, remember William was just 19 years old. He, and everyone else in the regiment, would have been apprehensive. They were facing Napoleon himself, for the very first time. Wellington was on the back foot, having been forced to make a tactical withdrawal the previous day. The 15th had had to cover that retreat.

12. Ibid, p 169.

13. Ibid, p 170

14. Cannon

15. WDS Journal, p170

16. Ibid, p170

17. Cannon

18. Parish Register, Little Dunkeld

© Murthly History Group