Dundonnachie Revisted

Thornie

Added on 21 May 2025

The text of a talk given to the Dunkeld & Birnam Historical Society

on Friday 4th March 2025

The subject of my talk this evening is Alexander Robertson of Dundonnachie. Often just simply “Dundonnachie”.

Obviously, I’m a bit trepdacious, talking about a Dunkeld hero. In Dunkeld. But I’m frae Murthly and we knew him too. He was our village’s first coal man.

Doubly anxious as I learned only a week ago tonight that Murray Robertson, Dundonnachie’s grandnephew gave a talk on this subject in 1992.

Anyone from then in tonight?

At the end of John Ford’s movie The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, a minor character, a news reporter, for whom the whole story has been told in flashback, says “When the fact becomes legend, we print the legend.”

And as an historian that has always garred me. The facts are always more telling and very often more interesting than the legend.

Dundonnachie achieved this status in his own lifetime. His exploits were already mythic while he was still trying, over and over and, sadly, over and over and over again, to get redress through the courts.

I’ll start with an example of this, from the Dundee Courier, in September 1875 which reprinted a short article from the London Pictorial World. Without any explanation or context. It was just filler, for a newspaper desperate for copy . . . Even so, the sub-editor should have known better. I bet a lot of readers saw that facts had been turned inside out:

There has just been released from a London prison a personage of some notoriety. I allude to the so-called Highland chieftain, Mr Robertson, or "Dundonnachie." This man has led a remarkable career.

He inhabited a quaint cottage near Birnam, in Perthshire (pictured); he wrote books on philosophy, and gave effect to his deductions by inciting the populace of Dunkeld to riot; he applied for a chair in one of the universities; and then showed his sense of defeat by opening a coal store,

[Wouldn’t the better story be the real one - that a coal merchant aspired to the Chair of Moral Philosophy at a prestigious university?]

… He ran through his coals and then went to London, where he was mixed up in what was known as the "Murthly Succession Case." In London also he contrived to publish a libel upon a solicitor, for which he was sentenced to a year's imprisonment. But failing health and high official interest enabled him to secure his release at the expiration of eight months of the period for which he was incarcerated. Dundonnachie is quite a Rob Roy in his way— that is, in respect of a powerful frame, a native disposition toward mischief, and a really gallant bearing in the field. But it is to be hoped that this remarkable man will be content with his achievements in the past. It would be little short of a national calamity if the chief were to return to his native heath, again to raise the cry of rebellion. Preserve us against such a catastrophe! I would suggest that Mr Robertson sit him down and write a book, not on philosophy, but on his own life.

This reminds me of the Morecambe and Wise sketch. When Eric sits down to play Grieg’s Piano Concerto for Andre Prevue. Much to Mr Previn’s horror. Not a whit abashed, Eric says “Listen, Sunshine. I’m playing all the right notes. But not necessarily in the right order.”

What follows, hopefully, are the notes in the right order . . .

Alexander Robertson was born on New Year’s Day, 1825 in Cross House, Dunkeld. To Alexander snr, a building contractor, and his wife Janet Douglas. The house had been in the family since 1766.

Young Alex was educated at the Royal School here, and probably at Perth Academy. I say probably as there is a story that he received his secondary education in Dumfries. But I haven’t been able to verify that.

At age 16 he got a job as a clerk in the Commercial Bank in Tay Terrace. Later a temperance hotel and now, very emphatically, not a temperance establishment. (I’m thinking back to the 1980s and a conversation with the late proprietor, Derek Reid, who said being in a temperance hotel was like washing your feet with your socks on).

In 1845, he was promoted to accountant and transferred to the Cromarty branch. The story has since grown legs that, as this was the bank Hugh Miller worked in, he mentored the young Alexander and encouraged his iconoclastic writing. Again, there is no evidence for this. And it’s very unlikely as Miller had left Cromarty for Edinburgh 6 years previously and was busy editing The Witness there.

There is evidence, however, of the Dundonnachie stubbornness. Of refusal to brook an argument. As he had a stramash with the branch manager and quit.

In 1847, the Robertsons bought a 60-ton sloop, the Dunkeld, registered in Perth. It was built in 1835 for James Brodie, who named the vessel. For Alexander the name was just a happy coincidence.

Dunkeld carried timber and timber products up and down the east coast of Scotland and England.

We are not quite sure when Alexander went into business for himself as it’s not clear when he left Cromarty for Perth. I don’t find any trace of him in either Cromarty, Dunkeld or Perth in the 1851 Census.

In 1853, aged 28, he burst into print with Barriers to the National Prosperity of Scotland: Or an inquiry into the root of some modern evils. (Published in Edinburgh by Johnstone & Hunter).

Over 300 pages of densely worded arguments summed up in a quotation on the title page:

“The conversion of small holdings into large farms, which ruined Rome, has destroyed Scotland.”

A quotation from Jules Michelet (1798 -1874) author of the Histoire de France, and the man who coined the term ‘Renaissance’ to describe the period when culture in Europe moved away from that of the Middle Ages.

The book is largely about three evils: The Law of Entail, the Game laws, and the Law of Hypothec (which gave landlords the right to possess a tenant’s stock in lieu of payment of rent. If you couldn’t pay your rent the landlord could take your cattle, horses, implements etc, leaving you destitute without the tools of your trade.)

The concentration of the land in the hands of a few has meant nobles “instead of being first defenders of the country, have ever been its biggest pests.”

Naturally, he published such an incendiary tome under a pseudonym, 'R Alister'. The book was generally well received, though not among the entailed class.

The Marquis of Breadalbane rose to the bait and responded to a review in the PA with a letter saying he wasn’t guilty of the things he was being accused of.

R Alister took this letter and published it in a pamphlet, “Extermination of the Scottish Peasantry” with his lengthy rebuttal of the rebuttal.

“If you have not been actuated by a desire to banish the people of Breadalbane out of the country, prove it by facts and figures, not by roundabout statements beside the point.”

He went on to say: The Marquis’ late father raised 2300 men at the last war, 1600 from the Breadalbane estates. Now you couldn’t find 150 there.

“Breadalbane has evaded the question as to why that is, if not the sweeping of his lands of cottars. But game of all sorts has increased by 100-fold.“

The Marquis responded by trying to buy up all copies of the pamphlet.

Alexander then took a sideways leap into Metaphysics, publishing “Belief in special providences” in 1854, before returning to the evils wrought on the rural population by clearance minded landowners with “Where are the Highlanders?” In 1856.

But also, in 1856 business opportunities were opening up. By this time Alexander had a small business in Prieston Road, Bankfoot. Suddenly this was sidelined by the opening of the Perth to Dunkeld railway. He quickly applied to the P&DR directors for the contracts to operate coal and wood businesses at Murthly and Birnam stations. Oh, not just the businesses, he wanted a monopoly on the supply of both.

The directors gave him the contract for coal only at Murthly. Coal and wood at Birnam. But no monopoly.

The following year, Alexander really got going . . . thanks to an entitled landowner.

Sir William Drummond Stewart had benefited hugely from the Law of Entail, a second son who’d inherited a vast estate, incorporating Airntully, Murthly, Birnam, Strathbraan and Grandtully. 35,000 acres stretching from just outside Stanley all the way to the edge of Aberfeldy. And all from a document drawn up before his death in 1720 by a distant cousin, John Stewart, Auld Grantully.

But Sir William still wasn’t a fan. In fact, he tried to break the entail on the Murthly estate from beyond the grave. [But that’s a story for another day.]

When the Law of Entail was ammended in 1848 allowing proprietors to give building feus to individuals and businesses, known as the Rutherford Amendment, he gleefully responded by applying to the courts for the right to parcel up most of Birnam into saleable lots. Saleable within the terms of the Amendment: 99-year leases; after which? Well, that was a problem for future generations.

In 1857, Alexander got a 99-year building feu for: a smithy, 4 houses, 1 apartment block, a granary, a 5-stall stable, and storage sheds for wood and coal. Sir William stipulated the buildings be slated and to the value of £500. (Which was a simple yardstick for ensuring everything was robustly constructed, well laid out - in an era when invoices were spelled out to the ha’penny.)

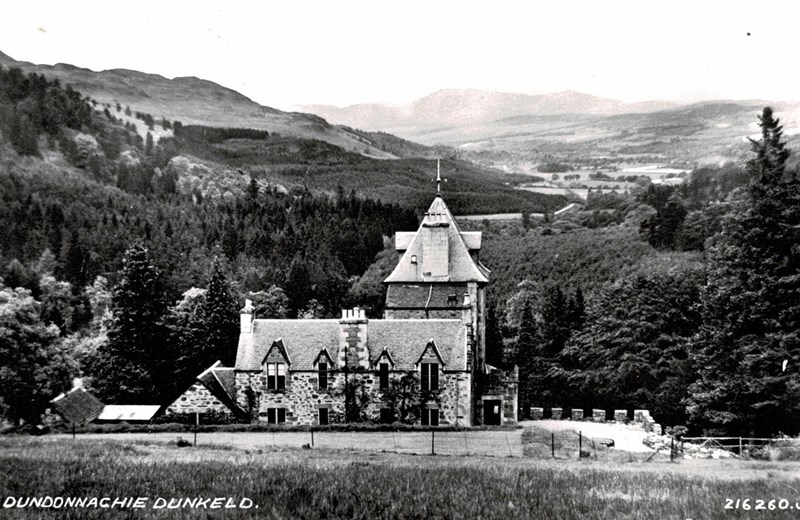

In 1859, he took out a feu for 11/2 acres of Tomgarrow Wood for a three-storey towered dwelling with coach house, stables and offices. This would be ‘Dundonnachie’ or as the Pictorial World would have it “a quaint cottage near Birnam”.

In 1860, he added 4 more houses, a bakehouse and 2 shops to the area of Birnam now known as New Feus.

In 1861, he applied for a feu on land directly opposite Murthly station to build a house and shop. However, during construction he asked Sir William to rescind the feu and settled for £200 cash for the partly erected building and all materials on the site.

And the first tenant of ‘Dundonnachie’ wasn’t Dundonnachie but a London banker, William Walter Cargill at a rent of £150 pa. Cargill was an agent for the Provincial Government of Otago in New Zealand, helping to implement a well-funded programme encouraging immigration from Scotland.

Was Alexander in danger of turning into Icarus, rising too high too fast? For whatever reason, on Census night 1861 Alexander was lodging at 9 Atholl St., Dunkeld. His occupation was given as ‘coal merchant’.

Then in 1862, out of the blue, he married Kate Stewart, a farmer’s daughter from Kingussie.

We don’t hear much from him until 1864 when he published “The Laws of Thought”. Nothing less than a wholly new, simplified form of Metaphysics, sometimes known as ‘proving the existence of God by mathematical means’. It seemed to be well received by the press and went through several impressions.

On the strength of that he applied for the vacant Chair of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow. For which he offered three justifications:

1 I am able to show that atheism and scepticism involve contradictions and may therefore be negatived.

2 That I can produce a mathematical demonstration of the existence of God. The solution of this problem, which has hitherto baffled metaphysicians, will revolutionise philosophy.)

3 That I can treat philosophy as an exact science. (At present it is taught merely as a rule of thumb, or according to the whim of each professor.)

Should the patrons desire evidence in support of these qualifications – which no other candidate will pretend to – I shall gladly afford satisfactory proof of their validity.

I regret to say Glasgow, a byword for empirical scientific research and education, rather let the side down, preferring the candidate who only had blind faith in the existence of God to one who had the maths to prove it.

Undaunted, this Alexander of Parnassus got back to work and produced an even more ambitious effort, published in 1866. “The Philosophy of the Unconditioned”.

This was too much for the Rev. James Morrison DD, perhaps the foremost theologian of the time. His review in the Evangelical Repository was one of “the most scathing bits of literary vivisection ever performed”, according to Henry Dryerre in his biographical sketch of Dundonnachie for Stormont Worthies.

Luckily, Dundonnachie saw reason. Accepting Morrison’s judgement, he bowed off from the metaphysical stage. In his next publication he would revert to type: as scourge of the parasitical land-owning class.

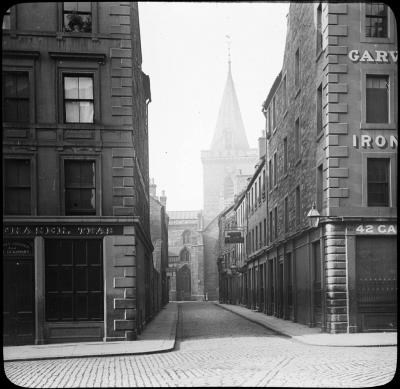

Reading Dryerre, one can’t help suspecting he thought this might all have been a giant hoax. A Unified Theory of Moral Philosophy? Reducing Metaphysics to a simple take it or leave it proposition? He for one couldn’t take it seriously. And it’s precisely at this point in his biographical sketch that he mentions regular Friday nights in the back parlour of the 'Black Bull Inn' in Perth’s Kirkgate (on the right, half way down in the picture below).

Dundonnachie would be there with his friend, Robert Whittet, the publisher, whose printing office was just across the way in Old Ship Close. Dryerre then worked as a compositor for Whittet. Together they would all, he wrote, revise the “proofs” over a mutchkin of usquebaugh.

1867 was the year everything changed for Robertson. Things set in motion years before came to a head.

After 20 years trading in timber with the Dunkeld the Robertsons sold their sloop to Thomas Scott. Did Alexander need an injection of cash for his businesses? Blowing off rhetorical steam in the Black Bull of a Friday night wasn’t necessarily harmful. But was he paying enough attention to business?

In March he gave the inaugural lecture of the Highland Economic Society in the Religious Institution Rooms in Glasgow. Announcing himself as the Society’s President he said the association had been formed to gather and disseminate correct statistical information regarding conditions in the Highlands. The lecture was another excoriation of greedy landlords entitled “Our Deer Forests”.

More time away from Birnam New Feus. When other merchants, such as Thomas Ellis and James Reid, were coming to the fore. And Birnam, though growing, still only had a small population.

Then the simmering outrage of the guid fowk of Dunkeld and Birnam over the tolls on Dunkeld Bridge boiled over. There was a public meeting in the Masons’ Hall (now Royal Hotel) and Robertson was asked to convene a small committee to investigate the Duke of Atholl’s claim that 43 years’ worth of tolls still hadn’t paid off his debts.

I’m not going to rehash the Pontage Riots here tonight. We all know the judgement of History doesn’t fall in the duke’s favour. I’m more interested in the consequences for Alexander Robertson. What if it was in the persona of R Alister he attended that meeting and agreed to write the report and, subsequently, contributed a series of political pamphlets lambasting the duke? From home. Would the results not have been better for Alexander Robertson, general merchant? And Kate.

History got Robertson’s other alter ego, Dundonnachie, instead. The Rob Roy figure of the Pictorial World sketch. Physically imposing but with a cudgel instead of a broadsword. Bullish, belligerent, pugnacious, the fiery orator . . .

The committee’s report was published in 1868. (By Alexander’s 'Black Bull' buddy, Robert Whittet.)

Apart from the subsequent civil disobedience, vandalism and rioting, in 1869 Alexander obviously felt all was still going well. For he asked Sir William for the lease of 10.5 acres of Tomgarrow Wood behind ‘Dundonnachie’, that quaint cottage near Birnam.

Then in January 1870 he was arrested for slandering Sheriff Barclay. You don’t have to be a conspiracy theorist to find this sequence odd: late in 1869 Dundonnachie writes to the Lord Chancelor complaining that Barclay is biased in favour of the duke; he then doubles down on that and writes virtually the same letter to the Home Secretary. Neither takes any public action. Then at a meeting on 3rd January Dundonnachie reports back to those assembled, quoting the letters, effectively repeating that Barclay is biased. A reporter from the PA is present, has good shorthand and prints the account verbatim on the 6th. Result: Dundonnachie is arrested on the 12th.

At the subsequent trial, the best the Law could come up with is that Alexander Robertson “murmured” i.e. slandered a judge. That is, to find a charge that would stick, they disinterred a law from the reign of James V, last used in judicial anger 300 years before.

He was found guilty, given 1 month in jail and a fine of £50. Or two months. There was no question that he could find the £50; and if he couldn’t, the money would have been raised from the committee and others. Instinctively, Dundonnachie took one for the Cause and played the martyr card. He opted for the full two months.

Many were unimpressed with Barclay’s actions. As the Strathearn Herald put it: “When professed Christian men fly to the law or let others do it for them, to vindicate their character, we have a strong suspicion there is something wrong with the accuser . . . and depend upon it, the public are quick to see through such acts.”

Imprisoned for two months; away from his businesses; Robertson’s creditors moved in. He was declared bankrupt.

On his release from Perth prison in early May he was given a hero’s welcome. Placed in a carriage he was dragged all the way along the Edinburgh Road right to Bridge of Earn and back, with thousands lining the streets and a pipe band playing. At one point, the horses were given the rest of the morning off and supporters took over. The carriage eventually made it to Carmichael’s Temperance Hotel in St John’s Street where a breakfast was laid on for 50 men, including friends from all around the country.

During his speech, Dundonnachie spoke of the court action.

This was “an outrage against my liberty that I have not ceased to harp and grudge against.”

And it would dominate his life for the next 20 years. A ceaseless round of litigation, court case after court case. Many of his attempts at redress were stymied because, as an undischarged bankrupt, he could not post what the legal profession calls a ‘bond of caution’ that is, prove he could meet the expenses of a civil action if the case went against him.

Some, like Dryerre, spoke admiringly of his grasp of the Law, of his ability to handle his own defence, of his oratory.

The fact is he didn’t win a single case.

After taking a beat lasting a week in Perth, perhaps making efforts to comfort and console Kate who after all, and through no fault of hers had also lost everything, the Robertsons returned to Birnam.

Another way of looking at it could be that after hiding out in Perth for a week, Alexander came home, like Tam O’Shanter, to face his Kate “Gathering her brows like gathering a storm/Nursing her wrath to keep it warm.” And why shouldn’t she; through no fault of hers she’d lost everything.

Reading the newspaper reports I’m inclined to think Kate remained in Birnam and wasn’t in Perth that week.

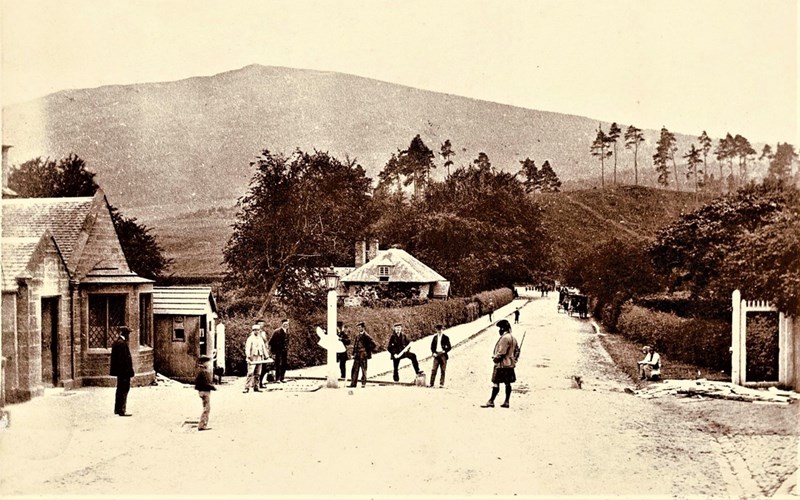

Again, it was home to a hero’s welcome. By train to Murthly accompanied by two members of the Dunkeld Bridge Committee (Perth branch). No mention of Kate. Then a carriage ride through Sir William’s grounds past Murthly Castle to the edge of the village. Where hundreds had gathered with flags and banners, and a pipe band in full Highland fig played ‘Hail to the Chief’. The horses were told to take a roll in the grass, and the carriage was pulled with the ropes that had pulled down the toll gates the rest of the way to Birnam Hotel by the jubilant crowd.

At the hotel there were more speeches. This time Dundonnachie stated he would not take an active part in further agitation to remove the pontage. There was then a vote of thanks for his past exertions and one of sympathy for his present position.

The newspaper report finished conventionally. “In the evening Mr and Mrs Robertson went privately to Dundonnachie House.”

Except that they didn’t. Couldn’t. The House was let at the time to the Earl of Kinnoull and Family.

For so it was reported when the House, the properties in the New Feus – the hale jing bang in fact – were put up for sale by public roup in July.

The successful bidders were John and Catherine Borrie and James Reid, grocers and ironmongers in Birnam.

There had been many collections taken up to provide Dundonnachie with some funds in recognition of all he had done in the struggle to abolish the duke’s pontage. His friends on the committee were canny enough not to be able to find this undischarged bankrupt in their midst and so resolved to hand over all the money realised, £466 2/7d, to the trustees of the marriage contract of Mrs Robertson.

And that’s the last we hear of Kate. Until March 1882 when Lord Fraser granted a divorce in the action by Katherine Stewart against Alexander Robertson.

On census night 1871, Alexander Robertson was alone again, in a lodging. This time his occupation was given as Author of Metaphysics.

He took a steamer to New York in 1881. There’s not much evidence to go on but Murray Robertson was told he lectured successfully and popularly on Scottish customs, folklore and song. Both in the States and in Canada. Robertson himself claimed to have edited the New York Produce Exchange Bulletin for a time.

If he had worn the kilt to any of the charity balls regularly given in the Produce Exchange’s impressive atrium, I’m sure there would have been no want of partners.

Chronicling America is the Library of Congress’ powerful digitised database covering just about every American newspaper since 1756. I could find an account of Dundonnachie’s assault on Lord Inglis leading to incarceration in the Lunatic Wing of Perth Prison, carried in the Delaware Gazette in 1891. (Of which, more later.) And several newspapers carried the inaccurate obituary put out by the London Globe in 1893. But no mention of a lecture tour.

He was back in Edinburgh in 1883. The Napier Commission had been set up that year by Gladstone’s government under Francis, 10th Lord Napier with a remit to, ‘Enquire into the conditions of the crofters and cottars in the Highland and Islands of Scotland and all matters affecting the same or relating thereto.’

It was headed by six landowners, including Sir Kenneth Mackenzie of Gairloch, owner of 43,000 acres of deer forest, and a Gaelic scholar known among the crofters as Lord Colonsay’s lackey. The Commission could and did call on expert witnesses of which Alexander Robertson, journalist, aged 58, residing in Edinburgh, was one. Journalist, not as president of the Highland Economic Society, which I think was rather short-lived.

Well, on the 24th of October Dundonnachie took the stand and gave them both barrels in a long, long statement full of facts, data that he said had been collected throughout the Highlands. He was less than impressed with “the idea of the national resources being altogether wasted for the grovelling excitement of deer slaughtering”. (I like to think he was looking Sir Kenneth Mackenzie with his 43,000 acres of deer, forest straight in the eye as he said this.)

It was an impressive performance, a distillation of all his political writing on the urgent need for land reform taken down and entered into the record.

Satisfying as that must have been, it did not ease his need for personal justice, for a proper hearing in a court of law.

From the litany of litigation conducted by and upon Dundonnachie over the 20 years since his sequestration three cases stand out:

The time he sued Queen Victoria for £100,000. Well, go big or go home, eh. Unsuccessful.

In January 1875, he was had up in the Old Court, London for publishing a defamatory libel on a solicitor, Mr Padstow. He and Padstow had agreed on a fee of £1,000 for Dundonnachie’s local knowledge of the Murthly Succession Case. With a total of £4,000 to come his way if the case was successful. In the end the deal soured and Dundonnachie ending up calling Padstow an unmitigated scoundrel.

He defended himself. To no avail. In fact, his plea of justification went against him, and his sentence was increased to 12 months. At the time he was lodging in digs in Holloway Rd. Effectively swapping those for, as it turned out, nine months only in Holloway Prison (which at that time was a mixed sex facility).

The third stand out court case came about in 1891. At that time Dundonnachie was back in Edinburgh, still trying to get redress for the injustice of that murmuring sentence. He resorted to knocking the hat off Lord President Inglis as he was leaving the Court of Session. He was arrested and admitted the action but said he had no intention of causing harm. He just wanted his case to be heard.

Well, that wasn’t going to happen. The powers that be had him medically examined, and he was found to be suffering from Monomania, and so unfit to plead. Therefore, unfit to be tried. Therefore, no reason for the aged and infirm Lord Inglis to be called to court and cross examined by Dundonnachie.

Defence Counsel at the High Court argued that the trial should nevertheless take place. There was no precedent for insanity being used by the prosecution as a bar to trial when Counsel for the defence opposed it. Said plea was rejected and the Lord Justice Clerk ordered Alexander Robertson to be detained at Her Majesty’s pleasure i.e for life in the Lunatic Wing of Perth Prison.

There was no big public outcry at this. However, friends in Glasgow, Edinburgh and elsewhere lobbied newspapers on his behalf. He was visited in prison and a reporter found him to be lucid, dignified, completely normal on every topic, including the assault on Lord Inglis.

Henry Labouchere MP, writing in The Truth (his influential radical journal) said:

Several of my Scotch readers have during the last few weeks appealed me to keep the case of the unfortunate man " Dundonnachie" before the public, and the only reason I have not hitherto referred to it is that I have been hoping to see some active steps taken on his behalf in Scotland. Dundonnachie earned a good title to the gratitude of his countrymen by a long and costly fight with the Duke Athole in defence of public rights. There is not a particle of evidence on which any impartial tribunal would have pronounced him a dangerous lunatic, and his condemnation and imprisonment for life as a criminal lunatic is a disgrace.

This piece was reprinted in the Dundee Courier on the 19th of August.

Without admitting to any pressure, the Secretary of State reviewed his case and Alexander Robertson was released on 21st December, after nine months detention.

One of his first actions was to sue the doctors who had examined him and pronounced him insane.

Another unsuccessful piece of litigation.

Dundonnachie visited Dunkeld for the last time one week after his mother, Janet died at Bridgend House. (Which Alexander snr had built in 1828.) He moved between Edinburgh and Glasgow for a time before settling in digs at 76 South Kinning St near Glasgow’s Kinning Park. His radicalism flared one final time in a pamphlet entitled “How they got the land: Or the origin, nature and incidence of the Land Tax”, published in 1892.

Alexander Robertson died in Glasgow’s Western Infirmary on 29th October 1893 six weeks after a diagnosis of senile decay. His profession was given as Journalist. The death certificate also mentioned that he was formerly married to Kate Stewart.

Dundonnachie finally came home on 1st November in a plain white coffin accompanied by his brothers John and Thomas and his nephews, carried by train to Birnam station. He was interred in the precincts of Dunkeld Cathedral.

Henry Labouchere wrote the best epitaph —Dundonnachie, when in his prime, was an eloquent platform speaker and a forcible writer, and, if he had never concerned himself with the Dunkeld Bridge grievance (or even if he had conducted the agitation with more discretion), he would probably have found his way into Parliament. He had the courage to profess and to advocate the most advanced Radical principles at a time when they were exceedingly unfashionable and in a district where all the influence was on the Tory side, so that a really Liberal tradesman or farmer was then regarded as a social outcast.

Alexander Robertson’s legacy is the 1878 Roads and Bridges Act which led, a year later, to the toll gates on Dunkeld Bridge being quietly removed overnight on 15th May.

He wasn’t wrong about the evils of Entail, Game laws or the Law of Hypothec, either.