Why The Jorums Got Their Name

Thornie

Added on 29 August 2025

No one now knows why a small chapel was dedicated to St Jerome at Hillhead, above Dunkeld. Or when. The mystery deepens as it is the only one dedicated to him in Scotland.

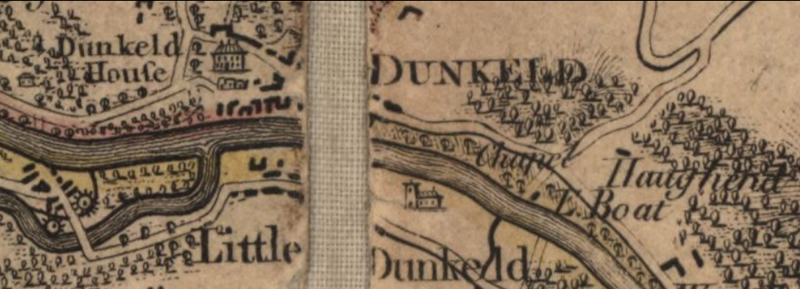

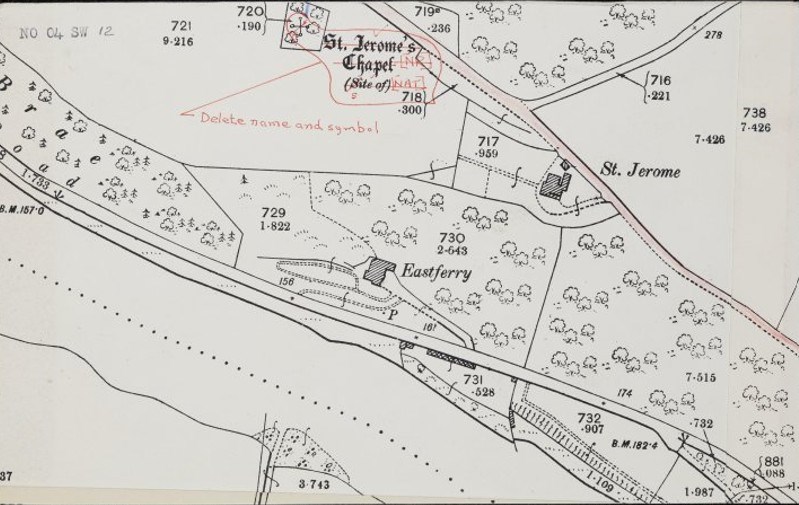

The chapel was first mapped in the 1st edition Ordnance Survey map of the area. [ Stobie’s map of 1783 below references a chapel in roughly the right location, but the placing of the text is misleading. It very probably means the kirk of Little Dunkeld, directly beneath and across the River Tay.]

The surveyor’s notes collected in OS Name Book vol 13,1 covering Perthshire, in 18591 show that some local ministers attested to the spelling. However, the only actual information given is a direct quotation from the New Statistical Account (NSA) which appeared in 1845:

There was another small chapel, called the Red Chapel, not far from St. Ninians, built on the top of the eminence east of the town called Hillhead, which was dedicated to St. Jerome. The chapel was principally erected for the inhabitants of Fungarth. The building is now levelled; but its site is enclosed by a stone wall. From the name of the saint, the people of Fungarth are ludicrously called to this day Jorums.

The stone wall went some time ago. In 1959, the OS resurveyed the area and made a clear instruction the site was to be substantially downgraded on the subsequent map.

Observant readers will have spotted that no one has suggested a date. The closest attempt, on the old Canmore site (now www.trove.scot) is ‘medieval’.

But if we stick to answering two questions:

· Why St Jerome; and

· Why the vicinity of Dunkeld

Then we’ll get to within 20 years of When? Maybe.

Let’s start with the man himself.

Saint Jerome (c.346 – 420) is principally known for his translation of the Bible from Hebrew into Latin. Known as the Vulgate version, it wasn’t the first such attempt and certainly parts of it were controversial but, eventually, it was accepted as the best and was for centuries the official version for the Roman Catholic Church. Jerome was a remarkably learned man, and a lot is known about him and his writings. (You can find a detailed biography here.) A scholar, but remarkably disputatious. (Even for a religious scholar.) Kind, a loyal friend and generous with what little he had, but ferocious in an argument.

Which is why whenever you see a classical painting of him it will generally include a lion (or what some Renaissance artist who had never seen one hoped looked like a lion). For the legend goes that one evening when Jerome was in discussion with some monks a lion loped up to the group. Everyone but yer man was out of there . . . doors, windows, whatever. Jerome spotted that the lion was extending its great paw, dumbly asking for help. He saw a large thorn among its claws and quickly pulled it out. The lion thereafter was his constant companion.

Never happened? You’re right, and likely not just because that’s a straight lift from the much earlier Aesop fable Androcles and the Lion. However, the story speaks to his insight - in spotting the lion wasn’t the threat it appeared to be; and to his kindness, in relieving it of the thorn. It also equates him with the qualities of the king of beasts, which can look remarkably docile (often pictured in a domestic setting with a totally unbothered lamb) until reminded it needs to be a lion.

Medieval clerics in Scotland as elsewhere would have known of St Jerome and the Lion. It was included in The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints by Jacobus de Voragine, published in 1260 and, throughout the late Middle Ages, the most popular read after the Holy Bible. But the big cat’s is not the spoor we should be following . . .

One such cleric was Gavin Douglas (c1474 – 1522). Along with Henryson and Dunbar, he is remembered as one of three hugely influential makars (poets writing chiefly in Scots) in the 16th century. His Eneados, completed in 1513, was the first full and faithful translation of a major work of classical antiquity into Scots. (Or any Germanic language for that matter.) Not just a rendering of Virgil’s Aeneid, each book or section had a distinct and original verse Prologue written by Douglas. It became a marvel of the age, continuing to captivate right down to the 20th century. CS Lewis said of it: “Here a great story is greatly told and set off with original embellishments which are all good—all either delightful or interesting—in their diverse ways."

This work references St Jerome both indirectly and directly. Indirectly: they both admired Virgil’s style and quoted him frequently (although that went against the grain for Jerome’s contemporaries who considered Virgil a pagan, a ‘Gentile’). Directly: Douglas explicitly adopted Jerome’s maxim about translation – sense for sense rather than word for word. Even more directly, in his Prologue to Book XIII of the Aeneid Douglas writes of having a dream or vision of St Jerome. Which Priscilla Bawcutt2 specifically links to this painting by Francesco Botticini.

And then, St Jerome is the patron saint of translators.

Although Douglas’ Eneados was not published in his lifetime (not until 1553, in fact) there were increasing numbers of copies soon after 1513. His scribe (secretary) Matthew Geddes made several copies immediately and may have commissioned others to do likewise. How many? Well, five manuscript copies have survived. There is one in Trinity College, Cambridge (dated 1525) two in Edinburgh University (dated 1527 & 1535), one in Lambeth Palace (1545) and one at Longleat, the Marquess of Bath’s home (1547). But the attrition rate of manuscripts following the Reformation is likely to have been high. If for no other reason than parts of it would have been considered papist and obscene. The 1553 print edition, pre-Reformation, was itself heavily altered through anti Roman Catholic ‘bias’, to remove references to the Virgin Mary and Purgatory. Additionally, 66 lines of poetry describing the amours of Didio and Aeneas were considered too steamy to be published.

Eneados was to be Douglas’s last literary achievement. He had a day job, provost of the collegiate church of St Giles in Edinburgh, a middling position in the clerical hierarchy which didn’t interfere over much with his writing. But in 1513, the Scottish king, James IV, led his army south to do battle with the English at Flodden. With superiority in numbers, and holding the high ground, the battle was his lose. And, verily, he did.

Scotland’s hierarchy, from James IV down, was ripped to bits there on 9th September. The ‘Floors’ we’ed awa that day included senior bishops and abbots. Several key positions, including the see of St Andrews, were suddenly available. Of this Gavin took note. Scotland quickly moved from being a country in mourning, effectively leaderless as James V was only a child, to one governed by hot-tempered ambition. And lust.

Gavin lost his elder brothers, George and William, at Flodden. So, when their father died later that year although his nephew, Archibald became the 6th Earl of Angus, Gavin, about to turn 40, became the senior Douglas. Perforce, by events and family, he also became a player in the ensuing political turmoil. Young Archie, “a wytless fuyll” according to his uncle, was already setting his cap at Margaret Tudor, widow of James, and mother of the young king. (They married in August 1514 and quickly had a daughter.) Which immediately put Gavin in the Queen’s party–against that of John, Duke of Albany. Many of the surviving nobles wanted the stability of having Albany, closest male in line to the throne anyway, as governor of the realm and tutor to the king. Margaret was but a woman, English, and sister to Henry VIII.

Which brings us to Dunkeld.

When Gavin helped Margaret secure the regency, she rewarded him with the abbacy of Arbroath and, in 1515, made him Bishop of Dunkeld. Which office got him into a world of bother with the Lords Temporal. The Scottish Parliament had the last word on such appointments and jealously guarded that right.

Now, Margaret Tudor might not have known of this, Gavin, being but a wumman, and English. But you ken, don’t you? That’s why we’re condemning you to the pain of outlawry. (And because we can’t touch the king’s mum.)

Bishop Douglas was warded (imprisoned) for a year and moved from castle to castle–Edinburgh to St Andrews, to Dunbar (my that was a cold one) and back to Edinburgh. When eventually released in 1516 and with his appointment reconfirmed, Douglas then found his way into Dunkeld barred by an armed band. Andrew, brother of the Earl of Athole had claimed the Bishopric for himself. And had put archers on the roofs of the town and the Cathedral tower to back it up.

Rivers of ink were spilled rather than blood in the ensuing struggle: both sides went to court. The Pope was even involved at one point. When the legal dust settled, Andrew had been paid off and Douglas was free to enter the bishop’s palace. “The churchmen and the whole country around obtained peace and the bishop, though burdened by debt [who do you think paid Andrew to go away], was able to devote himself to good works.” (Rentale Dunkeldense3) Principal among these was completion of the bridge over the River Tay. Bishop Brown, Gavin’s predecessor had begun that project in 1510 but had only seen one arch and the piers of two others in place. Douglas raised more money, somehow, and “continued it in so creditable a fashion that in a short time there was passage for the country traffic as well as pedestrians.” (RD p334)

However, Bishop Douglas did not have much time for good works at home as he was ever more embroiled in the political churn over the next few years. In 1517, he was in France, with Albany, to conduct negotiations which ended in the Treaty of Rouen. (Renewing the Auld Alliance and pledging mutual military assistance against the English.) Back in Scotland, with ambitions of his own to secure the Bishopric of St Andrews, he was forced to side with his nephew against both Margaret (who was now less than happy with her priapic, unfaithfu, scheming husband and suing for divorce) and Albany. Which resulted in him losing Dunkeld in 1521. He went to the English court on Archibald’s behalf, seeking aid to help oust Albany, but that came to nothing. While there he was taken by the plague and died in 1522.

All of which has moved us a long way from the chapel of St Jerome. But you will see that Bishop Douglas probably did not have the time in his brief but hectic sojourn in Dunkeld for a little chapel.

He was, though, the inspiration for the dedication, without a doubt.

So, who then was the instigator? And when?

It is unlikely to have been his successor, George Crichton, who if remembered at all it will be for his comment during the trial of Dean Forrest for heresy, “I thank God I never knew either the Old or the New Testament, and yet have prospered well enough.”

Bishop Douglas rewarded Matthew Geddes with the prebend of Tibbermore. That of Fungorth and Hillhead was already held by Robert Boswell (c 1486). Probably from 1505, according to the Rentale Dunkeldense.He was a son of David Boswell, 2nd of Balmuto in Fife, by his second marriage, to Margaret Sinclair. (And yes, these were forerunners of the Auchinleck Boswells that would, much later, produce that famous diarist and biographer.) Robert’s great grandmother on his mother’s side was Egidia Jill Douglas. Gavin Douglas’ aunt was also called Egidia Jill, the name recurring down the generations, giving them a blood connection. Which in itself may have been enough to engender the dedication, but it is possible-stroke-likely that Boswell had also read one of the Geddes copies of Eneados—and was inspired acknowledge his kinsman in this manner.

1560 is the cut-off point as to when. No one was dedicating Catholic chapels after the Reformation. Not until 1845, when Sir William Drummond Stewart of Murthly completed work on the chapel of St Anthony the Eremite. Which was nationally celebrated as the first Catholic church to be consecrated since 1560.

However, the feuars of Fungorth after Robert Boswell up until 1560, known to us through the Grandtully Muniments,5 although any of them could have commissioned the work, have no obvious connection with Bishop Douglas or St Jerome.

Money on Bobbie . . .

The chapel site is an intriguing one, worthy of archaeological investigation. Not least because it is small, contained and easily accessible from Dunkeld. Just right for the Young Archaeologist’s Club.

And who knows, perhaps they’ll find definitive evidence. After all, St Jerome is also patron saint of archaeologists.

SOURCES

1. https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/virtual-volumes/volume-images/volume_data-OS1-25-13/REX01689?image_number=34&search_token=.

2. “Gavin Douglas: A Critical Survey” by Priscilla Bawcutt (Edinburgh UP 1976) p 110.

3. Rentale Dunkeldense 1505-1517, Scottish History Society Second Series, Vol. 10, Edinburgh 1915, p 349.

4. A prebend was a source of income for a clergyman associated with a cathedral or collegiate church. As pre-reformation cathedrals were land rich this usually took the form of rents from a collection of small farms. Information on Robert Boswall’s (Boswell) holding can be found in RD p349.

5. Specifically, summaries of grants and charters covering the estates of Murthly, Grandtully and Strathbraan and additional land holdings compiled by Sir William Fraser and held in the archives of Murthly Castle.

© Paul McLennan